The Woodruff School’s Lab Sequence: Developing Workplace-Ready Engineers Through Scenario-Based Systems Investigation

February 6, 2025

By Chloe Arrington

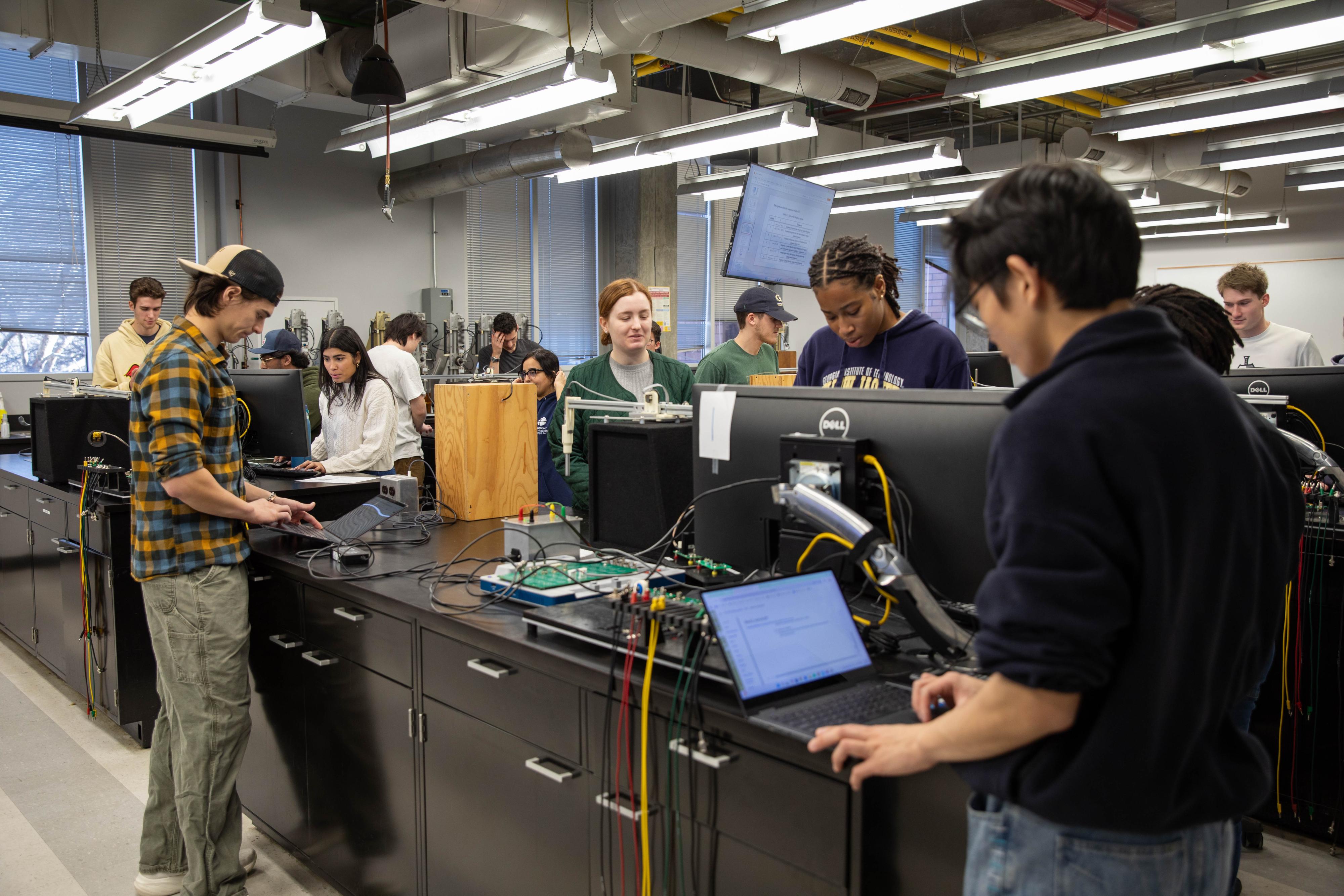

Gone are the days of boring “cookbook” style lab courses—where students mindlessly follow directives to collect data, perform analysis, and parrot back results without meaningful thought. Now the Woodruff School’s Lab Sequence—Experimental Methods and Technical Communication followed by Systems Laboratory—aims to produce workplace-ready engineers, capable of complex system-level investigation and communication of actionable conclusions targeted toward both executive and technical audiences.

The new course progression, a result of collaboration between Director of Interactive Learning David MacNair and Frank K. Webb Chair in Communications Jill Fennell, places students into roles at an engineering faux consulting firm—playfully named Burdell, Inc.—as they advance through scenarios of increasing complexity that simulate an employment journey: moving from newly hired experimental technicians to system engineers responsible for guiding high-stakes decision-making.

Across the sequence, students are taught the following tools, all while investigating technical topics from across the wide spectrum of mechanical engineering:

- Engineering Experimentation (“How do I characterize what is going on in the real world?”)

- Engineering Investigation (“How does theory help me explain real world behavior, and when does it fall short?”)

- Engineering Communication (“How do I convince stakeholders of my conclusions in ways that best suit their needs?”)

Engineering Discernment vs. Technical Demonstration

"Many people imagine labs as demonstration-oriented exercises where a manual tells you, ‘Set knob A to 10, knob B to 5, and then read from dial C. Plug that number into an equation and write a report about the result.’ There is very little learning there," said MacNair. "It's more important that students learn an investigation process, leveraging experimentation and engineering discernment to logically connect a client’s needs to actionable conclusions.”

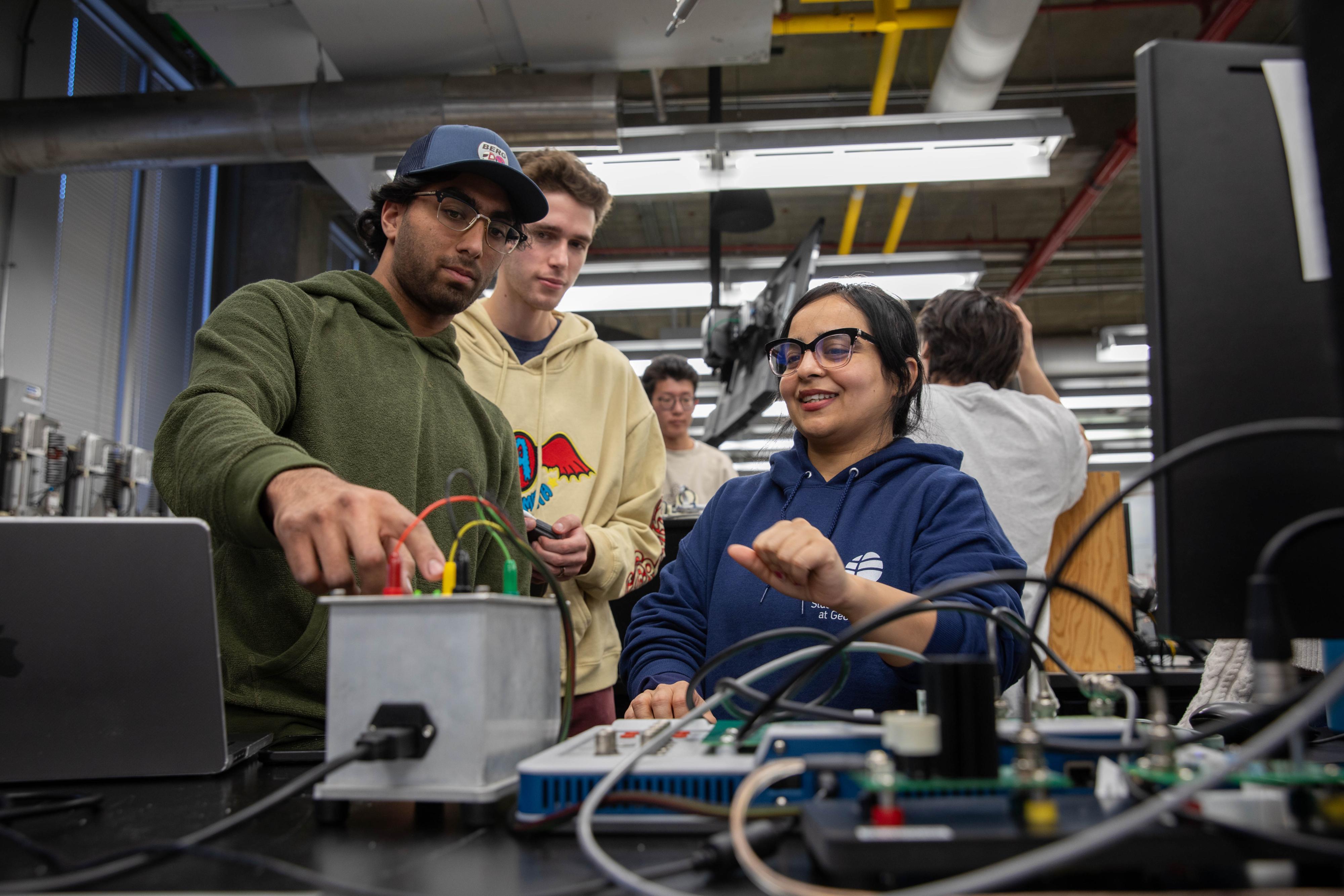

Students are primarily responsible for designing key details of the lab experience themselves that produce their final deliverable, much like the autonomy they would have when dealing with a client. One project students complete is a stress/strain experiment. In their scenario, they analyze the device performing the experiment (testing high-strain elements like climbing slings and low-strain metal components such as bolts) instead of the items tested by the device. The rig has intentional issues for academic consideration, and students must use their knowledge and exploration to determine the errors occurring for the client. Their findings are presented the way they would be in a workplace, emphasizing the clear communication of the data and results to the hypothetical client.

"We want to develop their engineering judgment," said Fennell. "We are trying to shift the bar of what it means to create industry-ready engineers by fostering their ability to determine what data is usable and needs communicating."

Fourth-year mechanical engineering student Marina Godinez has enjoyed the challenge of directly applying her knowledge and the investigative process. "The information we are given is not super straightforward, which is pretty accurate for how it is in real life. It comes with challenges, but we get to use our engineering judgment and problem-solving skills," she said.

This unique course design is not standard practice in other schools and is regarded by students as a great advantage.

"It was surprising how much the faculty emphasized the client-to-engineer relationship and how important it is to consolidate the technical data and language in an easily consumable way," said student Nolan Kurtzer about the Experimental Methods and Technical Communication course.

Students taking Systems Laboratory are expected to analyze complete systems through experimentation to determine the system's capabilities (whether they meet specifications) and when assumptions are appropriate. One project that students are tasked with focuses on an internal combustion engine. In this scenario, students perform a complex work/energy analysis on an engine to experimentally derive the system's properties. Students are given basic details in the form of an email from their client and, like working engineers, design and execute any testing that needs to be done and present their findings to the client.

Creating Information Designers to Inform Decision-Makers

Beyond data collection and analysis, the lab sequence trains students to become effective information designers. In both courses, students are challenged to distill complex technical findings into intuitive and actionable insights that will inform their clients’ decisions via short executive summary reports. This involves prioritizing data, choosing the most effective methods for presentation (such as visualizations), and framing results in ways that align with the client’s decision-making needs.

"In the Webb Program, we tell students that it’s an engineer’s job to communicate information to their audience with the lowest cognitive load while still remaining trustworthy and actionable,” said Fennell. “This sequence puts the responsibility on students to determine how best to balance these needs within a very short report.”

By embedding students in simulated consulting roles at Burdell, Inc., the lab sequence offers a hands-on approach to mastering engineering judgment and communication, demonstrating that technical skill and communication skill are inextricably intertwined. As students make technical decisions in the lab, they also must plan how they can shape the information for the audience. Graduates leave with more than technical skills—they possess the discernment and adaptability needed to succeed as professional engineers who can not only understand and interpret data but also communicate its value effectively to those who depend on it for critical decisions.